In the hushed pre-dawn light of a misty forest, a motion-sensitive camera silently captures the intimate grooming ritual of a snow leopard—an animal so elusive it was once called the "ghost of the mountains." This moment, frozen in time and pixels, is more than a stunning image; it is a data point, a behavioral insight, and a testament to how technology is fundamentally rewriting humanity’s relationship with the wild. Wildlife photography has transcended its artistic and documentary origins to become a powerful, indispensable tool in the crusade for conservation, offering a raw, unvarnished, and deeply revealing look into the natural world.

The journey from the first cumbersome field cameras to today’s sophisticated digital arsenal is a story of relentless innovation. Early pioneers like George Shiras III used tripwires and massive, explosive-powered flash setups to capture blurry but groundbreaking images of nocturnal animals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was laborious, invasive, and yielded limited results. The digital revolution changed everything. The advent of high-resolution digital sensors, which perform exceptionally well in low-light conditions, was a quantum leap. Suddenly, photographers were no longer constrained by a finite number of film frames or the agonizing wait for development. They could shoot thousands of images, reviewing and adjusting settings on the fly to perfect a shot in the most challenging environments.

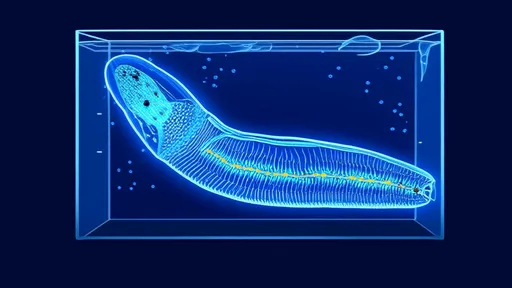

This technological evolution did not stop at the camera body. The development of robust, weather-sealed equipment allowed photographers to endure the harshest conditions, from torrential rainforest downpours to sub-zero arctic blizzards. Telephoto lenses grew longer, sharper, and more advanced, bringing distant subjects into breathtakingly intimate focus without disturbing their natural behaviors. But perhaps the most transformative innovations have been in the realm of remote and automated imaging. Camera traps, equipped with passive infrared (PIR) sensors, now sit sentinel for months on end, triggered by the body heat and movement of passing creatures. Drones provide a God’s-eye view, mapping vast migratory routes and accessing treacherous terrain without a human foot ever touching the ground. Underwater housings have turned the ocean’s depths into a new frontier for visual exploration. These are not merely tools for taking pictures; they are mechanical voyeurs granting us access to a world that has always existed just beyond the periphery of human perception.

The impact of this technological lens extends far beyond the gallery wall or the glossy pages of a magazine. It has become the eyes of science. For conservation biologists and ecologists, these images are not trophies; they are vital data. Camera trap projects generate millions of photographs that are analyzed, often with the help of artificial intelligence software trained to identify species and even individual animals based on unique markings like stripes or spots. This data provides irrefutable proof of a species’ presence in an area, allows for accurate population estimates, and maps territories with unprecedented precision. The photographic evidence is crucial for identifying biodiversity hotspots, understanding the impacts of climate change on animal behavior, and documenting the heartbreaking realities of poaching and human-wildlife conflict. A single image of a tiger with a snare wound or an elephant carcass stripped of its tusks can mobilize public opinion and political will in a way that a dry statistical report never could.

Furthermore, this technology has democratized discovery. Researchers can now monitor vast tracts of wilderness simultaneously and continuously, day and night. They have documented species thought to be extinct, like the Zanzibar leopard, and recorded never-before-seen behaviors, such as the tool-use of certain octopus species or the complex social interactions of solitary cats. This constant, silent observation reveals the truth of nature as a dynamic, interconnected web of life, rather than a series of isolated moments. It shows the chaos of a predator’s hunt, the tenderness of a mother’s care, and the stark struggle for survival in a rapidly changing world. The camera does not lie, and the truths it tells are forcing us to confront the consequences of our actions on the planet’s most vulnerable inhabitants.

Yet, for all its power, this technological gaze is not without its complexities and ethical dilemmas. The very act of observation can sometimes alter the behavior being observed—a concept known in physics as the observer effect, but equally applicable in ecology. The presence of a human, or even the persistent hum of a drone, can cause stress, alter feeding patterns, or drive animals away from critical habitats. The ethical photographer must constantly walk a fine line between revelation and intrusion, prioritizing the welfare of the subject over the acquisition of the shot. Guidelines established by conservation groups and professional photography associations stress maintaining a safe distance, minimizing time spent with sensitive species, and avoiding any action that could put an animal in danger or disrupt its natural life cycle.

There is also a danger in the seductive beauty of the imagery itself. High-definition perfection can sometimes create an aesthetic distance, sanitizing the raw, often brutal reality of nature. The blood of a hunt is rendered in vivid crimson, the fight for dominance becomes a perfectly composed ballet of muscle and will. There is a risk that the audience becomes a passive consumer of beauty, rather than an engaged witness to a reality that demands a response. The greatest wildlife photographers understand this. They use technology not to create a flawless fantasy, but to tell a true story—one that includes not only the majesty of a soaring eagle but also the desperation of a starving polar bear on a melting ice floe. Their work connects the viewer emotionally to the subject, bridging the gap between the human world and the wild, and inspiring not just awe, but empathy and a fierce desire to protect.

As we look to the future, the fusion of technology and wildlife imagery promises even deeper revelations. Developments in low-light and thermal imaging are peeling back the veil of darkness to show the nocturnal world in ever-greater detail. Tiny, minimally invasive cameras could offer glimpses into burrows and nests once considered impossible to film. AI is already being used to sort through millions of camera trap images at lightning speed, and machine learning algorithms may soon be able to predict animal movements and behaviors. Citizen science projects are engaging the global public, allowing anyone with a smartphone to contribute to data collection and species identification. This collective, technological witness is building the most comprehensive visual database of life on Earth ever assembled—a digital ark of evidence and wonder.

In the end, the truth revealed through the科技镜头 (technology lens) is multifaceted. It is a truth about the astonishing beauty and resilience of the natural world. It is a truth about the profound and often devastating impact of humanity. And most importantly, it is a truth that carries with it a immense responsibility. These images are a mirror held up to our planet, showing us what we have, what we are losing, and what we stand to lose forever. They are a silent alarm, a call to action written in light and shadow. The technology has given us the ability to see, but it is up to us to decide what we will do with that vision. The story of wildlife in the anthropocene is being written one photograph at a time, and the narrative is ours to change.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025