In the shadowy depths of South American rivers, a creature exists that seems to defy the very laws of nature as we understand them. The electric eel, or Electrophorus electricus, is not a true eel but a knife fish, a living paradox of serene grace and shocking power. For centuries, it has captivated scientists and laypeople alike, not for its appearance, but for its breathtaking ability to generate electricity. This is not a simple parlor trick of the animal kingdom; it is one of the most sophisticated and powerful biological power generation systems on Earth. The story of how this animal produces its charge is a profound narrative of evolutionary ingenuity, a tale written in the language of ions and membranes, of specialized cells and neural commands.

The foundation of this incredible ability lies not in magic, but in a fundamental principle of animal physiology: the resting membrane potential. Every single cell in every animal's body is a tiny, self-contained battery. This electrical charge, typically around -70 millivolts, is maintained by the delicate balance of ions—primarily sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+)—across the cell's lipid membrane. Protein pumps work tirelessly, like microscopic porters, to push sodium out and potassium in, creating a chemical and electrical gradient. This state of polarized readiness is the universal currency of the nervous system, used for communication between neurons and muscles. The electric eel's genius was in evolutionarily repurposing and massively scaling up this ubiquitous cellular machinery.

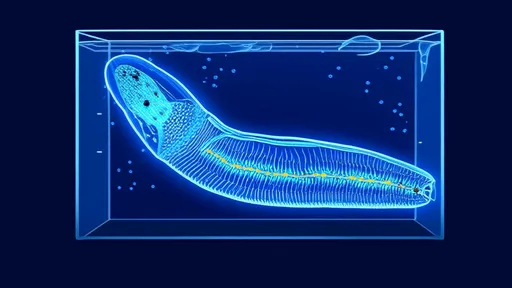

This scaling up was achieved through the development of a unique organ: the electrocyte. An electric eel possesses three such abdominal organs—the Main organ, the Hunter’s organ, and the Sachs’ organ—which together account for over 80% of its body length. An electrocyte is a modified muscle or nerve cell that has lost its ability to contract. Instead, its entire existence is dedicated to one function: flipping its electrical charge on command. Imagine billions of these disc-shaped cells, stacked in perfect series and parallel arrays, like the cells in a man-made battery. This precise biological engineering is the key to transforming a tiny cellular potential into a formidable external jolt.

The process of generating a high-voltage discharge is a symphony of cellular coordination. It begins with a signal from the eel's brain, traveling down specialized nerves to the electrocytes. This neural command triggers the opening of voltage-gated ion channels on one side of each flattened electrocyte. In an instant, a flood of sodium ions rushes into the cell, reversing the local charge from negative to positive. Crucially, the other side of the cell remains in its resting, negative state. This creates a dramatic potential difference across the single cell. While a single electrocyte might only contribute 150 millivolts, their true power is in their arrangement. Stacked in series, their voltages add up, much like linking numerous small batteries end-to-end to create a high-voltage pack. Furthermore, thousands of these stacks are arranged in parallel, combining their currents to deliver a powerful, sustained discharge rather than a brief, weak spark.

This sophisticated apparatus serves a dual purpose, dictating the nature of the eel's electrical output. For navigation and hunting in the murky, silt-laden waters it calls home, the eel emits low-voltage pulses, around 10 volts, almost continuously. This acts as a sophisticated biological radar system. The electric field distortions caused by nearby objects or prey allow the eel to build a three-dimensional electrical image of its surroundings. However, when prey is located, or the eel is threatened, it unleashes its famous high-voltage attack. This is not a single monolithical shock but a rapid volley of pulses. These pulses cause intense, involuntary muscle contractions in the target—a phenomenon known as tetanus—effectively paralyzing even large prey. Furthermore, the shock can directly activate motor neurons, bypassing the brain and forcing every muscle to fire at once. It is a precise and efficient tool for both sensing and subduing.

The sheer power involved is staggering. A large adult electric eel can generate shocks exceeding 860 volts and 1 ampere of current, resulting in a peak power output of nearly 860 watts, albeit for a very short duration of a few milliseconds. This is enough to stun a horse and is undoubtedly one of the most powerful electrical discharges in the animal kingdom. To put this into perspective, the eel is, for a fleeting moment, outputting enough power to briefly illuminate a dozen traditional incandescent light bulbs. This feat is made possible by the incredible synchronization of its electrocytes; all cells must fire within a fraction of a millisecond of each other. Any desynchronization would cause the currents to cancel each other out, resulting in a weak, ineffective discharge. The precision of this biological timing mechanism remains a subject of intense study.

Of course, wielding such power requires equally robust self-protection. How does the eel avoid electrocuting itself? Several ingenious adaptations provide immunity. Its vital organs—the brain and heart—are located close to the head and are heavily insulated by fatty tissue, far from the main electrical organs in the tail. The current itself takes the path of least resistance from the high-voltage positive pole in the head region to the negative pole in the tail, projecting the majority of the charge outward into the surrounding water. The water, rich in ions, is a far better conductor than the eel's own internal tissues. Furthermore, the shock duration is incredibly short, minimizing any damaging heating effect that could cook its own cells. It is a perfectly evolved system where offense, defense, and self-preservation are in exquisite balance.

The implications of the electric eel's biology extend far beyond the rivers of the Amazon. It stands as a powerful testament to the principles of evolution, demonstrating how complex and highly specialized organs can arise from the modification of existing structures—in this case, muscle cells. For biophysicists and engineers, the eel is a masterclass in efficient energy storage and discharge, offering inspiration for new designs in bio-batteries, capacitors, and power systems. In the field of medicine, understanding how electricity interacts with biological tissues has implications for neural therapies and pain management. The eel is more than a natural wonder; it is a living laboratory, a source of solutions to problems we are only beginning to articulate.

In conclusion, the electric eel’s power is not a mystical force but a magnificent product of biological evolution. It is the culmination of millions of years of refinement on a basic cellular principle, scaled and orchestrated to a degree that still inspires awe and scientific curiosity. From the minuscule ion channel to the coordinated fire of billions of cells, its story is a powerful reminder that some of the most advanced and efficient technologies on our planet were not invented in Silicon Valley, but evolved in the ancient, dark waters of the natural world.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025