In the quiet hum of a modern research lab, a team of engineers stares at a screen displaying the slow, graceful flap of a hummingbird's wings. This is not a nature documentary, but the birthplace of the next generation of micro-drones. Across the globe, another group studies the powerful, streamlined form of a kingfisher, not for ornithology, but to solve a sonic boom. This is biomimicry in action: the conscious emulation of nature's genius to solve human challenges. It is a field where the ancient wisdom of the natural world collides with cutting-edge technology, yielding solutions that are as elegant as they are effective. We are not just observing nature; we are becoming its most attentive students, learning to innovate from 3.8 billion years of research and development.

The story often begins with a simple, yet profound, observation. Take the kingfisher, for instance. For decades, Japan's high-speed Shinkansen trains faced a peculiar and noisy problem. Upon exiting tunnels at nearly 300 kilometers per hour, they would create a thunderous pressure wave, a sonic boom that could be heard miles away. Eiji Nakatsu, an engineer with a passion for birdwatching, saw a parallel between this problem and the kingfisher's dive. The bird plunges from the air, a low-resistance medium, into water, a high-resistance medium, with barely a splash. Its long, sharp beak is perfectly evolved to minimize shock and drag. Nakatsu and his team redesigned the train's nose to mimic this elegant beak. The result was not just a quieter train; it was 10% faster and used 15% less electricity. The solution was not found in a textbook of physics, but in the pages of a bird guide.

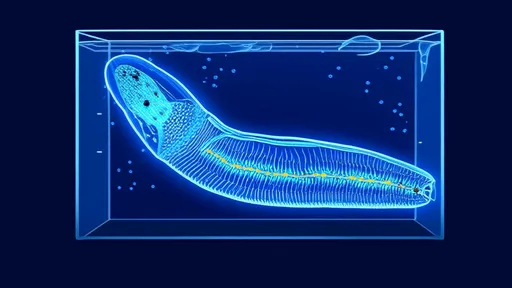

This principle of efficient movement extends far beyond trains. The enigmatic world of sharkskin has provided a blueprint for a revolution in fluid dynamics. To the touch, a shark's skin feels smooth, but under a microscope, it reveals a landscape of tiny, tooth-like scales called dermal denticles. These structures are arranged in patterns that channel water, reducing drag and preventing turbulent eddies from forming around the shark's body. This biological trick allows the predator to move with breathtaking speed and silence. Scientists have successfully replicated this microscopic texture into a material known as Sharklet. Its applications are vast. When applied to the hulls of ships and submarines, it significantly cuts through water resistance, saving immense amounts of fuel. Perhaps more astonishingly, this same texture, which repels water, also repels bacteria. The microscopic grooves make it incredibly difficult for bacterial colonies to adhere and spread, leading to the development of self-cleaning surfaces for hospitals, public spaces, and even medical devices, fighting superbugs with a design stolen from the deep.

Perhaps no creature has inspired more awe and imitation than the gecko. Its ability to scamper upside-down across a polished glass ceiling defies gravity and has puzzled scientists for centuries. The secret was finally uncovered not in its feet, but on its toes. Each pad is covered with millions of microscopic hairs called setae, each of which splits into hundreds of even smaller tips called spatulae. This fractal structure exploits weak atomic-level attractive forces known as van der Waals forces. The cumulative effect of billions of these tiny interactions creates a powerful, reversible adhesive. This discovery has sparked a wave of biomimetic innovation. Researchers have created synthetic adhesives that allow humans to scale glass walls like their reptilian muse. More practically, this technology is being developed for precise robotic grippers that can handle fragile objects, like semiconductor wafers or human organs, without crushing or dropping them, and for new medical bandages that can seal wounds without traditional adhesives that damage skin.

The pursuit of sustainable energy has also turned to the natural world for inspiration. The humble lotus leaf, long a symbol of purity in Eastern cultures, achieves its self-cleaning ability through a phenomenon called superhydrophobicity. Water doesn't just bead up on its surface; it rolls off like mercury, picking up and carrying away any dirt particles in its path. This is due to a complex nano-scale structure of wax-coated bumps that minimize the leaf's surface area for water to adhere to. Architects and material scientists are now engineering building surfaces, paints, and textiles that mimic this lotus effect. These surfaces stay cleaner for longer, reducing the need for chemical detergents and water for cleaning. On a larger scale, this principle is being applied to solar panels. By keeping them free of dust and grime, their efficiency is maintained without constant, resource-intensive washing, making solar energy more viable and sustainable.

Even the complex architecture of termite mounds, standing like ancient skyscrapers in the savannah heat, holds a lesson in climate control. The interior of a mound is a marvel of natural engineering, maintaining a constant, cool temperature despite extreme fluctuations outside. The insects achieve this not with air conditioning, but through a passive ventilation system of carefully arranged channels and chambers that harness wind and temperature differences to circulate air. Mick Pearce, an architect in Zimbabwe, took this concept to heart when designing the Eastgate Centre in Harare. Instead of conventional HVAC, the building uses a system of fans and vents that pull cool night air through floors and offices, flushing out warm air. The building's massive concrete structure acts as a thermal mass, stabilizing the temperature. The result is a building that uses less than 10% of the energy of a conventional building its size, proving that comfort does not have to come at an enormous environmental cost.

As we peer into the future, the frontier of biomimicry is shifting from macro-structures to the molecular and systemic level. Scientists are delving into the chemistry of mussel glue, a substance that sets underwater and holds with an iron grip, to develop new surgical adhesives and marine paints. The study of whale fins, with their unique bumpy leading edges (tubercles), is leading to more efficient wind turbine blades and hydroelectric turbines. The field is even expanding into organizational design, studying the collective intelligence of ant colonies and bee swarms to optimize logistics networks, data routing, and disaster response strategies. The potential is limitless, bounded only by our ability to observe, understand, and respectfully adapt the brilliance that surrounds us.

Biomimicry represents a fundamental shift in our relationship with the natural world. It moves us from seeing nature as a warehouse of resources to be extracted to a library of knowledge to be studied. It is a philosophy that values cooperation over conquest and elegance over force. In the precise dive of a kingfisher, the silent swim of a shark, and the gravity-defying grip of a gecko, we find not just animals, but master engineers. The most sustainable, efficient, and resilient technologies may not be ones we invent from scratch, but ones we discover, already perfected, in the living world around us. The challenge is no longer just one of engineering, but of humility and attention. The answers are here; we need only learn to see them.

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025

By /Aug 21, 2025